Thinking about the IT Organization of the Future

By M. Jordan, R. McClatchey

It’s a Different World Now:

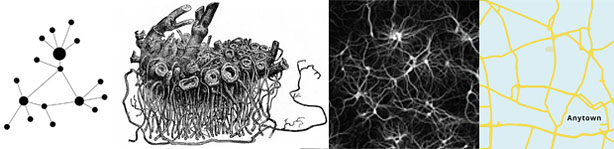

The Internet has decentralized everything it has touched. Like a rhizome, feeding

from and dispersing to all points at once, it has democratized information and power.

We no longer have to depend on a few elite sources for our news. Cloud computing means

that this very article can be written by two (or more) people, collaborating over

a network, using cloud-based software, and storing the result in that cloud. A short

time ago, this would have been a far more hierarchical process. This change has reached

an evolutionary force level, and there is no stopping it.

Rhizomes occur all across our experience. Named for a kind of plant structure without a central focus, we see this same structure in brains, population centers, or any sort of organic growth in complex systems, such as the Internet.

Like the Internet, this paradigm defines every aspect of the contemporary world, and it has radically redefined the ways large institutions serve their populations—and not necessarily for the better. Walt Mossberg, technology writer for The Wall Street Journal, characterizes large institutional IT departments as regressive; they have so much complexity and so much legacy that they're too slow and unwilling to react and change in a sphere that bears little resemblance to the world that created them. In fact, argues Dr. Timothy M. Chester, chief information officer for the University of Georgia, "There are real questions out there about whether or not central IT organizations can survive in this very decentralized world."

Chester talked about this important cultural shift and how it has affected information technology in a recent keynote speech presented to the Campus Technology Forum. His talk, entitled "The New Normal," outlined several key strategies that IT departments can use to engage, adapt, and ultimately flourish in this new environment.

IT can flourish in this arena, Chester explained to attendees, but he cautioned that IT organizations must realistically assess the situation before moving forward. He diagnosed this decentralization as permanent, and presented several strategies for engagement.

Adapting:

"We have to get past this notion that we need to control and be responsible for everything

at the institution" says Chester, "People bring their own disk storage, their own

email accounts, and their own consumer devices. No one has to come to us for basic

IT services anymore," he says, "so we have to get really comfortable with the idea

that we don't have to provide every service that an individual needs."

Rather than fight a losing battle for control in a self-service world, IT organizations need to adapt, according to Chester. He argues that adaptation requires relinquishing control in exchange for accountability from the newly empowered individuals.

"You trade control for accountability [...] through policy and other ways—you have to hold them accountable for what they do," Chester said in a recent interview. Indeed, a decentralized IT environment can potentially free up resources.

This also means seeking out and building on all the natural alliances for the IT organization—such as researchers, business staff, academic units, and library leadership—to exploit economies of scale and bring fresh ideas to the table. These allies can help facilitate the rigorous assessment and program reviews necessary to fully examine the state of IT and ensure accountability.

Building Credibility:

“In the current economic climate, the risks of centering organizational performance

on technical skills are magnified. When IT organizations think and act in ways that

communicate ‘IT is really about IT,’ this can have a profound—and negative—effect

on those outside IT,” Chester wrote in an article for EDUCAUSE Review Magazine. “When

this occurs, the role of the chief information officer may regress to the role of

a utility service manager.”

To get past that fate, it seems clear that IT organizations will have to look beyond technical knowledge, and adjust their hiring, professional development, and retention practices accordingly. Those skills are becoming increasingly transactional, suggests Chester, and while vital, these strategic services are easily quantified and benchmarked, perhaps even through third-party service level agreements.

The idea that technical skills are at the bottom of the competency ladder came from IT staff themselves, says Chester. Here is a portion of a recent interview on the topic:

Perhaps then, the real value in an IT organization is in its transformational role, where it brings technical and institutional knowledge to bear on true thought leadership in the field. Just as when we first started using these new technologies, and everything was about the technology for a while, the world changed when technology became the tool, subjugated by the more important task. So it is with IT, in a more general sense. While the trains need to "run on time,” as Chester puts it, we're still talking about trains, and trains exist to take you from A to B.

Credible conversations:

Transformational thought-leadership depends on a grounded understanding of the technical

and vice versa; it is a symbiotic relationship, with each aspect wholly dependent

upon the other.

Chester believes that separating thought-leadership from the transactional aspects of IT risks losing the potential for more credible conversations because deep expertise brings authority to the table. “I think institutions really short-circuit some of their potential when they disconnect thought-leadership around the effective use of IT from transactional excellence and the delivery of IT […] You have to have a leadership that understands […] that their credibility to play that broader advocacy and evangelism piece is entirely dependent on their ability to do the transactional piece.”

He points out that an IT staff, by the nature of their work all across a campus, might have a more realistic assessment of what’s going on out there than anyone. That’s a great wealth of expert knowledge, he says, that allows IT to conduct the kind of conversations that can shape policy in truly transformative ways.

Ultimately, Chester is very positive, and he believes that IT organizations can evolve with the times. "The future can be very bright for us," he says—and we believe him. He grasps the idea that technology is like the rhizome; it’s in a constant state of growth from many points, continuously decentralizing, with many nodes, all in the process of becoming. Our technological future is all around us, not just in some big iron box in a school's basement.